“Nature cannot be fooled.” –Dr Richard Feynman on the political inclination to put image over safety.

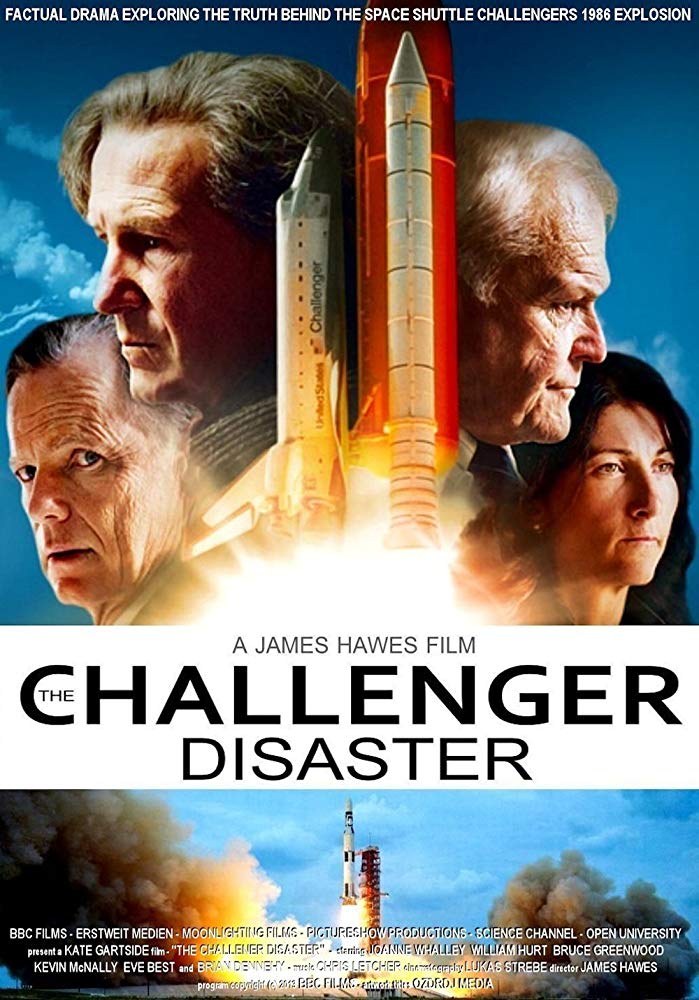

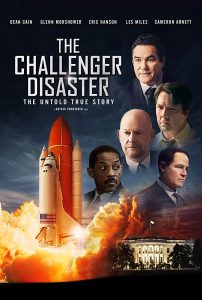

On a brisk January morning the 26th of 1986 the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated only 73 seconds after liftoff. The immediate fall-out brought on by engineers, management, and civilian consultants would ground the Space Shuttle fleet for at least three years. This review focuses on the two docudramas that were made: a 2013 direct-to-TV movie produced in conjunction with BBC, Open University, and The Science Channel called The Challenger that focuses on Dr. Richard Feynman’s contributions to the Rogers Commission investigating the accident. The second docudrama is a 2019 release that follows the lives of the engineers at Morton-Thiokol the night before the launch and in the days immediately following.

Both mo vies offer gems of their own, and while they are centered on the same event in time their stories are so different from each other it’s not an intellectually fair move to compare their cinematic qualities. Reviewing them in order I watched them: the 2019 edition gives a surreal glimpse into a much different NASA administration than was seen during the 60s and into the early 70s. One glaring difference is that in the early days at NASA all the engineering was being accomplished in-house by Von Braun’s team as far as the rocketry went. Since as early as the late 70s that department has become outsourced, and the initial company to win that contract was Morton-Thiokol (MT).

vies offer gems of their own, and while they are centered on the same event in time their stories are so different from each other it’s not an intellectually fair move to compare their cinematic qualities. Reviewing them in order I watched them: the 2019 edition gives a surreal glimpse into a much different NASA administration than was seen during the 60s and into the early 70s. One glaring difference is that in the early days at NASA all the engineering was being accomplished in-house by Von Braun’s team as far as the rocketry went. Since as early as the late 70s that department has become outsourced, and the initial company to win that contract was Morton-Thiokol (MT).

Much like 2016’s Hidden Figures the 2019 edition of the Challenger story does make use of a few composite characters, which makes sense considering at least a few of those engineers at MT would go on to become whistle-blowers, something NASA has never had to concern itself with until the Space Shuttle program. The character Adam played by up-and-comer Eric Hanson (Segfault, The Price of Fame) is essentially our protagonist; and there is a strong likelihood he may represent the top three whistle-blowers at MT, Brian Russell and Bob Ebeling and Roger Boisjoly. For between a quarter and half the movie Hanson’s character is spending the hours leading to January 28th doing everything he can to convince those “on the fence” engineers as well as the management at MT that the O-rings are not tested at temperatures as low as the expected temperatures would be at Cape Canaveral/Kennedy in Florida on the morning of the 28th.

Some of the more appalling parts of the movie are seeing the engineers squabbling with each other pedantically. In one nasty ad-hominem exchange Adam gets accused of being the pebble that gets caught in a shopping cart’s wheel and keeps the shopping cart from being able to move forward, at Adam’s insistence that the coming shuttle launch is simply not safe enough for the data they have. Adam’s response to this was to fire back, “And you’re the engineer who can’t design a shopping cart that can roll over the pebble.” I would have busted out laughing at that comeback had the implications of the movie not been so deeply in my mind. And, of course, the drama only continues from there. However, what begins to unfold in the first half of the movie is something quite revealing of NASA’s management, not to mention the management at MT. A historic conference call gets made between NASA’s administrators at Kennedy and Marshall Space Centers and the engineers and management at MT’s Utah plant.

As Adam tries to urge NASA’s chief administrator to delay until they have a confirmed warmer day to launch the admin fires back, “When do you want us to launch? Next April?” With NASA unable to launch without contractor approval, but still wanting to meet its own promise to Congress – a revelation not made in this film but was in the 2013 edition – they apply pressure to the admins at MT. Rather than see the issue from the engineering (and thus health and safety side) stance the management officials decide to fold and give NASA the administrative go-ahead against the engineers’ wishes. It was pretty disturbing watching that unfold.

All the engineers, nay management, are in agreement that the launch is simply too dangerous with the weather conditions. At one point Adam explains that they only have test data confirming launches as low as 54° F, since that’s the coldest NASA has ever launched a shuttle in its history. NASA’s administrators, not liking this response because they’ve already had to delay the STS-51-L mission several times, the latest of which was for a faulty sensor in the orbiter’s close-out hatch. By the time the engineers were able to fix it the launch window had already passed. “If they had launched the day before the mission was have been just fine,” Adam tells Finch Richards played by the versatile Glenn Morshower (Transformers: Dark of the Moon, 24). It’s Richards’ responsibility to determine if Adam is merely a corporate troublemaker, finger-pointer as opposed to a legitimate whistle-blower.

Finch’s opposition is played by the equally versatile Dean Cain (Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, Out of Time) whose responsibility it was to coach all the engineers who would go on to become whistle-blowers what to say both at the press and as far as how to handle and field all inquiries.

For me, the selling point of the 2019 edition would only amount to about 10 seconds or so when we get to see inside the crew compartment for a few seconds immediately following the shuttle’s disintegration and at least one of the astronaut’s struggle to activate their Emergency Oxygen System, and what that says about those final two and a half minutes the astronauts had before plummeting into the Atlantic – almost none of them if any, it is believed, died immediately upon the disintegration itself. Most, if not all, likely perished on impact into the Atlantic considering the sheer g-force the compartment would have been under. I recall when watching Gravity for the first time that it would really suck to get hurdled into space due to random junk coming at you from “nowhere” and no means of being retrieved. But watching the panic in the face of the crewmember I recall feeling a deeper sense of “oh, shit!” than any fictional account could come close to achieving, and, yes, that includes the legendary Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. I would rather have to combat a homicidal AI machine than experience those two and a half minutes of pure uncertainty.

And speaking of sensations that hit us “in the feels,” as revealing as I found the 2019 telling of the whistle-blowers’ story the 2013 edition is even more stark as to the revelations, implications and over-all explanations for why the Space Shuttle Program was in need of whistle-blowers at all.

The 2013 edition focuses more-so on the Rogers Presidential Committee that investigated the accident, but more specifically on Dr. Feynman’s contributions. Played by Oscar-winner William Hurt (Lost In Space, Humans), Feynman’s tenacious efforts to uncover what actually brought the Space Shuttle Challenger down were so impactful that even the chairman of the committee, William P. “Bill” Rogers played by Brian Dennehy (First Blood, Tommy Boy) was discovered to have told Neil Armstrong, also on the committee, “That Richard Feynman’s turning into a real pain in the ass.” In the movie he doesn’t say this to Neil, but to another composite character. There’s a scene when Feynman first shows up at NASA and gets introduced first to the United States’ first woman in space Dr. Sally Ride played by Eve Best (The King’s Speech, Nurse Jackie) and the composite character “fellow Physicist” Dr. Alton Kiel (sp?) played by Langley Kirkwood (Dredd, Banshee). Unfortunately, while his is a composite character, he is only billed as “avionics engineer.” When Feynman meets him, “Your name I recognize too, a fellow physicist.” Kiel responds, “Informally. I’ve been in Washington [DC] several years,” to which Feynman chuckles a bit and asks, “How’s the integrity?!” Now that made me laugh out loud and still does even when I go and re-watch the show. Having read Surely, you must be joking, Mr Feynman that was the kind of humor I’d expect from a personality like his, and I tend to agree with his philosophy about the integrity of politicians: they’re like arachnids, they’d eat their young to make a buck or pass a bill.

The 2013 edition starts within an hour of Challenger’s launch and interweaves that moment with one where Dr. Feynman is getting introduced at a Physics lecture hall where he’s about to put on the very show he does best – showing prospective physicists the importance of being able to conceptualize all the kinds of crazy Calculus formulae they’ll be subjected to in their futures before learning the theory, the formula; and the way he does it is nothing short of Feynman-brilliant.

As Feynman takes the stage, he wastes no time describing the mathematical explanation of the transition from potential to kinetic energy. The formula he uncovers looks completely Greek to anyone who has never had so much as an Algebra or Calculus class; I have studied both I barely got the gist of the formula before Feynman, seeing students starting to furiously scribble down the formula, tells them to stop, “Not till you know what it means.” Since the theory is only as good as its application Feynman prepares the demonstration by setting up the infamous bowling ball experiment. I won’t go into how it works because I do want you to watch the movie, but suffice to say his point is made loud and clear. He presses, what good would it have done them to write the formula down? “Make you feel pretty smart? But now you understand it.” While he is going through this philosophy of science his words are pulled into narration as we see the crew preparing for the trip to the launch pad and the Challenger launch. “What is science? Science is a way to teach how; something gets to be known, in as much as something can be known because nothing is known absolutely. That’s how to handle doubt and uncertainty.” It’s the line he delivers just before the disintegration that still gives me goose-bumps, “Science teaches us what the rules of evidence are; we mess with that at our peril.” Hurt does a phenomenal job nailing Feynman’s mannerisms, eccentricities, and even that famous New York accent that always pervaded Feynman’s speech patterns being from upstate New York.

As the 2013 edition was based on the collective efforts of Richard’s and Gweneth’s book What Do You Care What Other People Think we do get to see an incredible degree of insight into Feynman’s initial reluctance to join the committee, but then Gweneth played by Joanne Whalley (Willow, The Man Who Knew Too Little) counters with how his methodology in finding answers is exactly what would make him the perfect man for that committee, and boy was she correct. Much later in the film General Don Kutyna, played by the also highly versatile Bruce Greenwood (Star Trek, Thirteen Days), corroborates that sentiment as Feynman is the only genuinely independent scientist on the commission – everyone else, including Dr Ride, had some amount of their careers in space at risk depending on what they made known. Where the 2019 edition showed that there were certainly problems on MT’s end where the overall engineering and manufacturing of the SRBs were concerned the 2013 edition shows just how much arm-twisting and pressure NASA’s administration was putting on its own team-members, also another first.

One would think that with a disaster that was televised to the entire world NASA would be eager to have the Rogers Commission get started investigating right away, I and Feynman both seemed to. At the opening of the meeting Bill Rogers poses the idea that the Challenger shuttle, being composed of more than 2 million parts, may well be too complex of a machine to accurate pin down a single cause for the accident. Feynman’s own insistence that no matter how many parts may have been involved with the Space Shuttle that thanks to his path integral formulation any problem could have an infinite number of parts involved and one would still be able to use statistical analysis to predict the likelihood of any one of those parts involved as the culprit of the accident, “…whatever happened to Challenger an explanation can be found. Or what are we doing here if we don’t think it’s possible?” After handling a few more concerns as far as the best method to proceed with the investigation and how to handle press queries Bill Rogers strangely adjourns the meeting with the assertion that everyone, “Would reconvene in five days’ time, and enjoy Washington in the meantime.” The look on Feynman’s face was a cross of confusion and contempt; completely understandable since this was a guy who loathed wasting time for concerns of ceremony or political image.

Being the tenacious explorer, Feynman bypasses Chairman Rogers wishes (they weren’t orders after-all) and starts investigating on his own starting at the Marshall Flight Center. The discontentment of the engineers is palpable from the get-go. Like being the new “weirdo” at school Feynman takes his lunch and goes to sit at a table to start nomming at which point two of the engineers get up to walk away knowing precisely why Feynman was there. One of the engineers even goes as far as to say he’s got nothing to hide. Um, great?? It’s while sitting down to that lunch Feynman’s able to notice the body language on the two engineers remaining at the table upon asking them to come up with a number they believe accurately predicts the statistical likelihood of a launch failure. The two engineers kinda eye-ball each other for a moment. It’s just long enough that anyone who’s at all familiar with the Netflix show Lie to Me could tell you the two men were sweating their jobs. Why, though? Why should any engineer whose job it is to make the launch as safe as it can be for the astronauts to do their jobs ever fear the repercussions of being honest with an investigator about the concerns they might have as engineers about the products they were making?

As Feynman starts to inquire with one of the SRB engineers played by Nick Boraine (Homeland, Black Sails) about what must have happened the engineer believed the main engines to have been the culprit rather than the SRBs. When Feynman pressed for why that had to be the case the engineer replied that it couldn’t have been either of the SRBs since they couldn’t “fly with holes in them.” Just as Feynman believes he’s getting some cooperating the engineer stops mid-explanation with a paranoia creeping into his tone, “Look, I’m not ratting out any of my fellow engineers,” to which Feynman rebuttled that if answers aren’t provided and a cause isn’t found there will be no more jobs for any of those men. Truth!

As the story continues we get to see more into Feynman’s own quality of life. While he claimed to Gweneth only scenes earlier that he was “fit as a fiddle” he was unfortunately far from that. Turns out the exposure to the atom bomb he got along with everyone else at Los Alamos was creating football and similar-sized tumors that were affecting his kidney function. In multiple scenes he is seen all but wrapping himself around his room’s heater.

In the following scene he is with the full committee at the hangar where about 70-ish% of the debris from the wreckage has been collected and laid out for examination. The committee learns about the emergency oxygen having in fact been activated by at least a few of the crew. Rogers approached Feynman, while in the midst of examining some of the debris, about the visit to Marshall and strongly recommends how he prefers the committee stick together on the investigation. Feynman’s rebuttal is simply that he doesn’t agree with just standing around as the rest of the committee has essentially been ordered to do. “The other members are just showing respect, Dr Feynman.” Feynman, clearly indignified by Bill’s implication, fires back, “Are you saying I’m not? You understand the implications of the Oxygen being activated? I do; they had to do that themselves, which means they were still alive for some of those two minutes and 36 seconds before slamming into the ocean; Mr. Rogers, I’m an atheist. I personally doubt they were touching the face of God so I prefer to show my respect by finding the cause of their appalling deaths and not stand around looking sad.” Being a self-described agnostic I had to let out a small ovation for that sentiment. “I don’t know why you wanted me on this commission,” Feynman continued, “but now that I’m on it I have every intention of finding out what went wrong.” If you have ever worked on a speed-bag that was what I call the intellectual equivalent of an Iron Mike right-hook taking the speed bag off its ceiling! Again, from Feynman, “Ya know, I don’t know that NASA did a great job.” General Kutyna shoots him a look that I consider a glimmer of hope in the good General’s eye. The tension between Chairman Rogers and Feynman is definitively palpable. Question is why?

By the next scene we see a bond forming between Kutyna and Feynman, and from there it doesn’t take Kutyna long to “gently,” as can be accommodated for bringing a civilian in on a government project, express to the physicist how much his being an independent party gives him the most leverage for finding the answers above anyone else on the team including Dr Ride. “I’m invisible,” Feynman boasts a bit, “Invisible,” General Kutyna affirms, “but watch your six.” Not a military man Feynman asks him to clarify the metaphor, and Kutyna does just that. You’re invisible, but not beyond some amount of intervention if you push too hard in the wrong direction. For the duration of the film Kutyna makes a point to Feynman that NASA is not the same civilian organization it once was.

Feynman returns to Marshall Flight Center and this time around comes across even more unsettling information about the Challenger’s SRBs: pogo oscillation. After challenging one of the engineers at Marshall (a different one than he’d spoken to on his first visit to MFC) he began finding that the engineers were miss-classifying matters of a mission critical nature with lower levels of critical rankings. Unfortunately, Feynman’s impulsive nature gets him into a small pickle with Chairman Rogers when Feynman hastily jumps to the conclusion that the main engines were the problem as opposed to the SRB O-rings. Though not disclosed in the 2013 production Feynman was actually still correct that even while the O-rings were the immediate cause of STS-51-L’s accident the safety of the shuttle itself has been called into question several times by elite engineers. What’s more unfortunate is that the same design used on Space Shuttle Columbia would ultimately lead to its own disintegration upon re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere on February 1st, 2003 killing all of its crew members in a significantly more violent manner than anyone aboard Challenger would have experienced.

I could spend another four pages providing more and more break down into the 2013 movie, but perhaps one of my favorite scenes was the exchange between Feynman and Kutyna in the ladder’s garage as the good General was looking for the most “in one’s face” hint possible to direct Feynman’s attention to the O-rings. Kutyna’s first method was to use his own sports car and mentioned how it would make a great ride if the carburetor weren’t so problematic, suggesting that the O-rings always cause trouble in the cold. Greenwood doesn’t say this in the movie, but the book suggests Kutyna was actually a little more obvious than the movie suggests. While Feynman is admiring the car though not much of an enthusiast about sports cars, he and Kutyna talk a bit about Feynman’s own involvement in World War II back in the 40s and how Feynman must have had his share of government types. Feynman tells Kutyna that he had been responsible for determining how much fissionable material would be needed to produce the kind of blast Oppenheimer had in mind. “It’s not a good use of science.” Kutyna tried consoling him with, “Your efforts helped end the war.” Feynman gave off a scoffing chuckle. Even while Feynman might not have taken Kutyna’s hint in the garage the same engineer from Feynman’s first visit to Marshall Space Flight Center showed Feynman the O-rings of the SRBs, and finally Feynman, at least in the movie, is able to piece together the concern.

In the following scene there is a cross-over validation of the engineers for MT telling the committee that the engineers at MT were in disagreement about the approval of the launch. As Dr Ride points out that if the management at NASA was indeed warned by MT engineers, “The astronauts sure weren’t.” Even Feynman describes in his book how livid that made him.

I think what I found to be the most disturbing of all the revelations was when Kutyna takes Feynman to the Pentagon and has the eminent scientist sign a bunch of NDAs; Feynman would ultimately reveal in What Do You Care … was that in fact NASA, while still a chiefly civilian research agency in guise, had ultimately become absorbed into the military industrial complex (as seems to happen when a civilian government agency loses its crowd-funding), and thus its guise of being a civilian agency becomes merely a smoke screen. What becomes revealed is that while NASA may have gotten its start at the beginning of the Cold War and while we fulfilled Kennedy’s initiative of reaching the moon before the Russians, the Cold War was still in full swing. The US Air Force was still interested in deploying unmanned satellites to keep an eye on our overseas interests. “Paranoia,” Feynman calls. “Whatever you civilians are told we are still deep in the Cold War. NASA approaches Congress with a deal that seems to make great economic sense,” essentially use NASA’s Space Shuttle program as the sole vehicle into space. In theory it would save the taxpayers a boat load of money instead of having to build Falcon-heavy rockets that had to be rebuilt with every launch they could re-use the Space Shuttle as many times as needed to get the Air Force’s satellites in space. The tragedy folds over a new layer as NASA renegs on its promise to launch satellites and starts using the money instead for one PR stunt after another – in Challenger’s case: high school teacher Christa McAuliffe, who was sold on the falsehood that launch failures are at a ration of 1 in 100,000+, which Feynman would point out in the last day of the investigative committee that such odds are so ridiculously incalculable it would impossible that they could have derived that number from experimental data. At the end of this unveiling of sorts Feynman vents, “Upstairs you made me sign that classified information thing. So what’s going on, Kutyna? You’ve got me trapped. It would jeopardize national security: the Soviets learn we can’t launch anything in cold weather. You’ve been playing me from the beginning?” Seeing the exchange at that point between Kutyna and Dr Feynman was more than enough to raise the goose bumps for me, again. Feynman grows furious as he tells Kutyna, “I can’t do anyting with this. Don’t ever tell me anything I can’t open my mouth and blab to the world about,” but Kutyna, not ready to lose the battle to expose the shabby management NASA has fallen into is eager to help Dr Feynman find a way to bring the information to public’s eye. It’s there that Kutyna finally explains to Feynman how as a civilian he really is the one truly independent scientist on the whole committee. Dr Ride, Armstrong, everyone knows a lot of the puzzle, but no one knows the entire story.

After the Apollo program, specifically Apollo 17, many of the employees who worked at NASA felt the sting of downsizing as public interest in space exploration weigned in the years following that last Apollo mission. So by the late 70s, NASA becomes desperate to keep government funding flowing their way, Kutyna tells Feynamn. In a bold initiative NASA made a promise to Congress that they’ll send up a payload whenever needing, which it decides to dedicate to General Kutyna’s satellite deployment project.

Whether the statistical analysis Feynman had requested from the Marshall Space Flight Center’s engineers was figured out in the code by Feynman upfront or if the code phrase, “We think: Ivory Soap” in the movie it’s Gweneth that actually translates the code. “the old Ivory Soap ads, 99.4% pure.” Eureka! The Marshall engineers estimated the success analysis of any mission at only 99.4%, which is considerably less than the NASA management’s claim of 1 in 100,000 launches before a mission failure would happen.

In the final day of the investigation Feynman makes a point of how even some of the most complex ideas in nature can be demonstrated with easily comprehendible experiments. To make his point about O-ring resilience he used the same material the standard O-rings for the SRBs were made from, he pinched some into a C-clamp and immersed it in ice-cold water for a cuople of hours and successfully demonstrated, as Dr Ride and General Kutyna had long suspected, that at lower temperatures the O-rings do in fact lose their resilience and ability to expand as designed when subjected to freezing temperatures.

Over-all grade for the 2019 edition: 8

Over-all grade for the 2013 edition: 10